Excerpt from the Introduction to

Until Darwin: Science & the Origins of Race (2010)

[UNCORRECTED PROOF]

[UNCORRECTED PROOF]

Pickering & Chatto Publishers

21 Bloomsbury Way London WC1A 2TH E: info@pickeringchatto.co.uk

Hb: c.256pp: October 2010

978 1 84893 100 8: 234x156mm: £60.00/$99.00

978 1 84893 101 5

http://www.pickeringchatto.com/titles/1396-9781848931008-until-darwin-science-human-variety-and-the-origins-of-race

The complete text of this chapter can be found at:

https://www.academia.edu/230777/Until_Darwin_Science_Human_Variety_and_the_Origins_of_Race

Introduction

Ecce Homo or Slavery and Human Variety

Ecce Homo or Slavery and Human Variety

The history of science is a history of forgetting. It is the history of how scientific truth emerges from the murky cacophony of words and things that were once said and built, but are now silenced and buried. At the moment a regime of scientific truth coalesces, this cacophony is enveloped within a rational, ordered and yet arbitrary universal system. But we should pause to remember that the elements of this system were already present in the anarchy it replaced. For reasons of practicality, we are taught to forget the chaos which preceded contemporary knowledge. At the same time, those elements of wretched knowledge that we thought were finally repressed by truth continue to emerge over and over again. In 1999, for example, most of the sociologists and anthropologists in the United States and Canada received in the mail an edited version of a 300 page work purporting to prove the inferiority of Blacks and Asians relative to Whites. The book was by a tenured professor at a respected Canadian university and published reputable press associated with a major American university.

On the other hand, it is certainly true that many insightful critiques of the concept of race have already been produced. The best of these works carry on the tradition of examining race not as an essential aspect of bodies, but as a concept of power that is overdetermined by the ideology of everyday life. In this sense, they have made significant contributions to our understanding of the meaning ---or emptiness--- of race. There are divergent tendencies at play in these works. Some tend to ignore or insufficiently treat the scientific definition of race as a historical problem, or at least they do not delve very deeply into the longe duree of race. Other analyses are much more historical, but often present the concept of race solely in the context of the history of ideas. It is in these works that some argue that racialism is rational and ‘at times’ a useful tactic of those classified as racially inferior by the dominate ideology. Others suggest that racialism can only come from one source ---one people--- and no where else. Few if any of these works, even those histories of ideas, trace the concept of race along the entangled path that leads to the critique of science itself, choosing to reflect on philosophy and meaning. There is little attempt to continue the analysis through to its historical critique of truth. The scientific work is mentioned only in passing, but if reason and domination are connected, as they most certainly are, then the history of science must be of more than mere passing interest to the study of Human variety. Reason --- manifested through science and technological domination --- is central to understanding race. This is especially true because the philosophy of race after Spencer came to serve as an interpretive adjunct to the science of race, just as philosophy came to be the adjunct of science. In the final analysis, the place to find the origins of the ‘meaning’ of race is in the sciences of life, in the magnificent bio-social discourse that spans disciplines from Natural History to Sociology. An investigation here leads one to understand the emptiness of the concept, except in relation to the formations of ideologies which serve as apparatuses for the deployment of scientific knowledge and its subsequent accumulation. In the essay you are now holding and reading, the analysis of race is not about finding the correct view of essential characteristics. This essay is about how the social and biological sciences are invested with authority. In a more theoretical sense, this essay is an attempt to situate the study of race in the context of a more general study of bio-social discourse. There is no better expression of the ideological foundation of modern science than the history of the scientific classifications that form the parameters for most biological and sociological investigations of race and racial differences.

This essay suggests an avenue of research that might fill in a space made available by a variety of earlier work. An assumption that runs through much of this body of work is that the imperative to describe the experience of race can easily result in the distortion or elimination of the history of race. Relying on the description of this experience can make of the history of race appear as a series of obvious and easily recognizable events that led naturally and inevitably to the present. If "one must notice race" as some sociologists have claimed, then race must be seen not as metaphysical concept or reduced to the level of mere identity. Instead, what we have come to refer to as race is a landscape of conflict. The extent of this conflict is limited by a bio-social discourse on the meaning of being human. This meaning is supposedly manifested by racial differences which we believe are constitutive of what kind of human we are, if indeed allows that others are truly human. In the pages you are holding, race is examined not as a historical truth, but as a moment in the history of truth. This essay is an investigation into the scientific classification of human variety. It is an attempt to recover a past which has been forgotten or repressed by the very sciences of life and society whose origins are to be found in these forgotten errors.

To examine human variety in terms of the history of truth, requires that we understand the history of modern science and the history of race as inwoven histories. Does this mean that science is racist? Such a question rightly sounds absurd, but not for the reasons that the defenders of the privileges of scientific knowledge and the power of science would like us to believe, nor does the simplicity of the question negate its seriousness. To be sure a few scientists actively embrace racism, sexism, homophobia, etc., but the question is not whether science is racist. A more concrete question is: how does race function as a 'scientific ideology'? How has it successfully functioned as a scientific ideology for so long a time despite the considerable efforts that have been undertaken to make it a part of normal science. Race is a powerful expression of the attempt to fix the meaning of life and to determine its value. From their beginning, the human sciences have sought the fixed, unchanging meaning behind human diversity. Until Darwin, this meaning was not discussed in our terms of biological and cultural diversity because the naturalists did not think in those terms. Instead, what stood before them was not biology and culture but essentially one object of study which they understood as a history that was the playing out or unfolding of immanent and often racial determinations ---evolution as understood the preformist sense of the word. An acorn, as the old saying went, can only become an oak.

Historically, the language of race and the language of science reveal a continuity, even if the politics of this continuity is in constant flux. But the ability of science to fix ---however unstable and temporary this might be - the classification of human variety has contributed mightily to the establishment of the authority of science of life in our understanding the truth about human nature and society. The authority of science to construct the degenerate, the criminal, the genius, and the sexes as objects of knowledge is an authority intertwined with the scientific ideology of race and the administration of authority. This essay is an investigation into race only in so far as race exists as a scientific ideology which are, in effect, truths that are never quite true. i

One of many places to contribute to a broad project on the scientific study of human variety is the critical inquiry into the scientific classifications of human variety. One does this knowing that this is a question whose subject constantly refers it back to itself. One can not escape creating classifications at the same time that one undertakes a critical study of fundamental systems of classification. Nevertheless, the task here is not to develop a theory of race, but to ruthlessly critique race as a scientific ideology. This makes the investigation of the history of classifications and their place in scientific ideology absolutely necessary to our obsession with finding the meaning of race.

The history of science is the victim of a classification that simply it accepts, whereas the real problem is to discover why the classification exists, that is, to undertake a ‘critical history of classifications’. To accept without criticism a division of knowledge into disciplines prior to the ‘historical process’ in which those disciplines develop is to succumb to an ‘ideology’.iiIt is not that race is prior to class, sex or gender, nor is it a more essential foundation to the classification of human variety. We might have found all manner of differences on which to base our producing of human types and we have clearly used gender, class, and other cultural differences To argue for the priority of racial classifications would be to re-inscribe the hierarchy that we should be attempting to make uninhabitable. A critical investigation of the many classifications of human variety discloses the history of scientific attempts to establish race. It is a history that should unsettle our most basic assumptions about both race and science. Certainly, nothing less than our faith in an immutable identity is called into question. At the same time, the manner in which science has described race and used it as a means to understand humans calls into question its own authority. ‘The obsolete is condemned in the name of truth and objectivity. But what is now obsolete was once considered objectively true. Truth must submit itself to criticism and possible refutation or there is no science’.iii The process by which we come to place a value on race rests within a hierarchical classification of bodies, attributes, truths, and institutions. While classification is necessary for any production of knowledge, systems of classification also constrict and set the borders of acceptable knowledge. By investigating the scientific classification of human variety, we can begin to dismantle one of the ideological truths which we have since internalized and naturalized. This essay is not concerned with denouncing the disciplines or reproaching them for their errors. Any discipline rests upon its particular regimes of truth: the ‘report, naming, the narration of a Beginning, but also presentation, confirmation, explanation’.iv Often, this includes how a genius lived, a discovery was made, or a theory’s predicted outcome was put to the test and resulted in a group of texts that established both an entire horizon of knowledge and the mythical history of the discipline itself. In contrast to this, the perspective that ‘[c]lassification is a condition of knowledge, not knowledge itself, and knowledge in turn dissolves classification’v neatly captures the process by which the Natural History and political economy became the disciplines of biology and society.

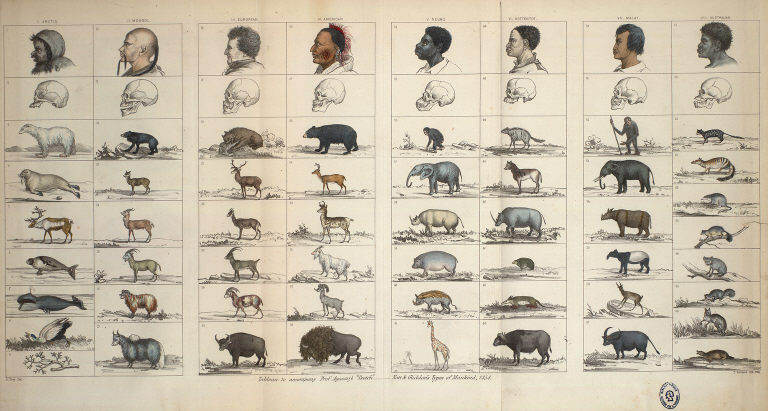

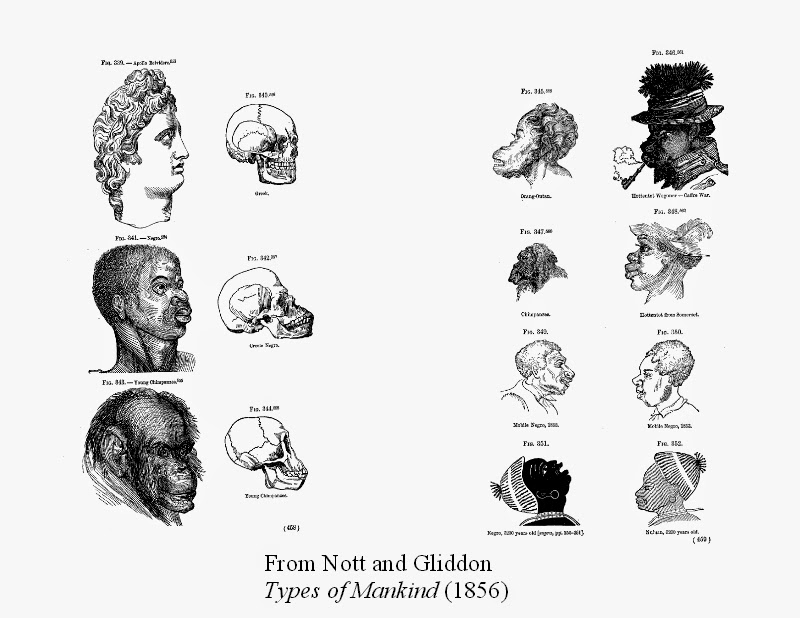

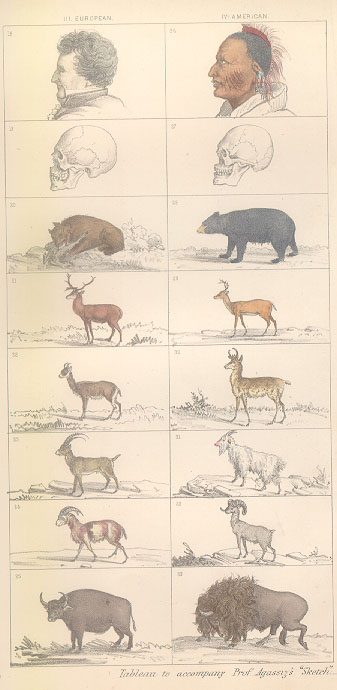

Smedley argued that "the identification of race with a breeding line or stock of animals carries with it certain implications for how Europeans came to view human groups."vi The very use of the term race placed an emphasis on innateness, on the unchanging and unalterable in humans. ‘The term ‘race’ made possible an easy analogy of inheritable and unchangeable features from breeding animals to human beings’.vii The morphology and behavior of humans defined and explained the animal as much, if not more, than the morphology and behavior of the animal explained the human. Race now served as a foundation for creating a new creature: "the European." As a category for classifying humans within a general classificatory chart or Table of Nature, race has had varied and contradictory meanings. It was not the case that new principles of biology were applied to society, but that nature became social at the same time that the social became natural. The belief that they constituted each other took on new meaning after humans were placed in the world by Linne, Cuvier, Darwin and Marx. If the cause of human variety could be found, it would be the explanation for the variety of nature. It is also true that insights gained from animal husbandry could be used to explain human variety. These tendencies are common in the work of Natural History that took ‘the species question’ as a central object of study.viii Indeed, from Natural History to biology, the quest to solve the species question was organized on the generally accepted assumption of multiple contemporary human species. The definition of species, a concept so central to the development of modern scientific thought, was determined within the context of the search for the origins of human variety.

It is not so much that race pervades everything, but that race is one mode of an all pervasive bio-social discourse. Race is said to speak through the living being, who is subordinate to the truth of race. In so speaking, race could be said to pervade the social relations of everyday life: master/slave; creditor/debtor; capitalist/worker; parent/child; etc. But to naturalize race in such a way gives weight to an empty concept and distracts us away from the apparatus of knowledge that speaks through and to race. This bio-social knowledge unites a) discourses on nature and life such as Natural History, biology, medicine, ecology, and their systems of classification; b) discourses on the forces of life, which are of two kinds: first the rational forces of Enlightenment ---like the universals of History, Consciousness, and Reason---and second, the irrational forces of the instincts, the mob, the anarchy of the social relations of capital, and the masses; c) discourses on the stability of society, or social inertia, such as the sociological writings on stability, progress, and degeneration. One might even hazard at this point to again use the word ideology.ix Beneath the argument in this essay is the assumption of a close relationship of authority and scientific ideologies. In one sense, the reader can take away from this work the most timid proposal, that scientific ideologies matter, that they have real effects in the world, and that they are a part of the social relations they describe. A critical analysis that addresses scientific ideology would be impossible if ideology was not located in the materiality of everyday life, i.e., if it did not find expression in the materiality of social relations. What could express this more than the taxonomy of ourselves? What better than the classification of human variety that unites Camper’s finding of beauty in the facial angle with your sideways glance at the suspicious or ‘out of place’ person walking through your neighborhood?

Chapter One delves into the importance of the Species Question itself and the singular importance the riddle of human variety held in its investigation. The question of the existence of species and their origins would be decided by first solving the problem of human variety. It was believed that human variety held the key to understanding why variety existed in Nature in general. We would finally know the reasons for our many differences in physiology, language, and progress towards civilization. Monogenism and the fixity of species had a uneasy coexistence when variety was obvious to any observer and needed explanation.

Chapter Two traces the shift from monogenism to polygenism, or the theory of multiple origins, i.e., the theory that each race originated at a different time and in a geographically isolated and unique locale. The monogenic theories were widely supported and derived most of this support from their seeming agreement with the Book of Genesis. Polygenic theories, on the other hand, were common amongst those who disputed the truthfulness of the Biblical creation story and who were busy building the first respected scientific theory of human origins from the new world. The popular height of the polygenic theory was the publication of Josiah Nott and George Gliddon’s Types of Mankind. Types of Mankind was a tribute to their friend and teacher Samuel J. Morton as well as an open repudiation of religion in favor of free scientific investigation. Such investigation lead them to proclaim that the polygenic origins of human variety. This chapter gives a general discussion of the American School and an account of the brief period before Darwin when polygenism was the predominate scientific theory of the origins and meaning of human variety. This theory falls before Darwin's explanation for a common origin of humans and the chapter which follows puts Darwin in the context of the species question and his intervention against the monogenic/polygenic discourses. Darwin’s title is itself an acknowledgment of the species question. It is suggested that when seen in the historical context of slavery and civil war, Darwin produced a sharp break not merely with polygenic theory, but with the entire discourse between the supporters of polygenic and monogenic theories. Darwin, it is argued, sought to not only to produce a new scientific truth, but also to put an end to the current scientific discourse on human origins: ‘... when the principle of evolution is generally accepted, as it surely will be before long, the dispute between the monogenists and polygenists will die a silent and unobserved death’x.....

....But these general statements on continuity are not particularly insightful or original, for it is a commonplace of our time that the question of chronology receives much serious analysis. Nor can these statements tell the story of how human variety came to be understood according to racial types. Pliny's ‘prodigious’ humans are humans. They are not deviations, degenerates, or deformities, nor are they the result of hybridization, etc. They are not signs or omens, representations or divine favor or wrath, etc. This is a fundamentally different conception of human variety from the Christian one. Monsters marked the limit of Nature, but prodigious varieties did not. What Marx found in capital Pliny found in nature: that the process of accumulation and reproduction marks its own limit.

In Aristotle's works human variety was not a defining characteristic of a particular historical period. The ambition was to define and classify humans through the doubled relation between polis and nature, and between humans and nature. It does not minimize this double relation to recognize that the social relations of master and slave is seen as fixed and permanent and allows race to take on a transhistorical presence, for a slave is now born to be a slave, and the master a master. The everyday social relation between humans in a polis transcends its material basis and comes to stand for all human relationships. On this point Marx and Nietzsche agree: a fundamental social relationship is that of creditor/debtor, and that this relationship has a history that could be excavated through critical and genealogical approaches. The basic social bond that we bring to light is all to often one of cruelty and cooperation - because breaking or transvaluing the already given social relation reproduces the same cruelty that brought it into existence in the first place.i The return of the repressed appears in its most concrete form: the cruelty of the relation never disappears, it simply comes to appear as nature itself, or as the very definition of what is natural in terms of human nature. Nature comes to embody the cruelty found in the State and in Nature and vis versa. ‘The welding of a hitherto unchecked and shapeless populace into a firm form was not only instituted by an act of violence but also carried to its conclusion by nothing but acts of violence---that the oldest ‘state’ thus appeared as a fearful tyranny, as an oppressive and remorseless machine, and went on working until this raw material of people and semi-animals was at last not only thoroughly kneaded and pliant, but also formed’.ii The relationship of slavery to our understanding of human variety is just one specific instance of the broader apparatus of cruelty and cooperation.iii

The complexity of its subject makes a work such as this one difficult and its conclusions ultimately tentative until such time as others take up the task. There are some similarities and alliances that one might expect, but there are also many that are surprising or ironic. What we can definitely say is that this complex arrangement of discourses and institutions producing ---and produced by--- the knowledge of human variety teems with continuities, discontinuities, dialectics, fanciful speculations, frauds, empirical observations, measurements, and classifications. At the very least we can conclude that out of this emerged the authority of the sciences of life and society: biology and sociology as the true sciences of Enlightenment. The assumption underlying this work is that the true meaning of human variety and its origins are like the Ghosts of Africa mentioned by Pliny at the end of his catalog of the notable varieties. He describes them as the species of human that vanish when approached.

The complete text of this chapter can be found at:

i ‘Scientific ideologies are explanatory systems that stray beyond their own borrowed norms of scientificity’. This is precisely why the history of science is really about the history of truth and error, and not falsity or false consciousness. ‘Scientific ideology is not to be confused with false science, magic, or religion. Like them, it derives its impetus from an unconscious need for direct access to the totality of being, but it is a belief that squints at an already instituted science whose prestige it recognizes and whose style it seeks to imitate’. Which is to say that a scientific ideology will persist until such time as an adjacent discipline demonstrates its potential contribution to ---and alignment with --- an established disciplinary knowledge. G. Canguilhem, Rationality and Ideology in the History of the Life Sciences (Cambridge: MIT Press 1989), p. 38.

ii M. Serres in Canguilhem, Rationality and Ideology in the History of the Life Sciences, p. 34.

iii Canguilhem, Rationality and Ideology in the History of the Life Sciences, p. 39.

iv M. Horkheimer and T. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: philosophical fragments (1947) (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), p. 8.

v M. Horkheimer and T. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, p. 182.

vi A. Smedley, Race in North America: origin and evolution of a worldview, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993), p. 40.

vii A. Smedley, Race in North America: origin and evolution of a worldview, p. 40.

viii ‘The questions before us at this time are – 1. What is a species? 2. Are species permanent? 3. What is the basis of variations in species?’ J.D. Dana, ‘Thoughts on Species’, American Journal of Science and Arts, 24 (1857), pp. 305-316, on p. 305.

ix Ideology is not merely the symbolic re-presentation of social production; it is present in every moment in the process of production and accumulation, in every movement, thought, sound, and gesture. Ideology is found in the discourses, technologies, and moralities of everyday life produced by the social relations of capital. The mystification of social conflicts lies in the production and commodification of desire in everyday life, since part of capitalist social production is given over to the production of desire itself (Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment 1969[1944]). Desire, especially the desire for one's own repression, is a social relation located "in the particular social character of the labor that produces them" (K. Marx, Capital, Volume One (New York: Penguin Classics, 1967), p.77.

x Darwin, Descent of Man, 1998 [1874]:188.

....

i K. Marx, Capital, pp. 439-454.

ii F. Nietzsche, On The Genealogy of Morals [and] Ecce Homo (1887-1888), ed. W. Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale ( New York: Vintage Books. 1969), p. 86.

iii B. R. Brown, ‘City without Walls: Notes on Terror and Terrorism’, Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination, 2:1 (2007), pp. 53-82.